本周,IMF国际货币基金组织——这是一个产生于1944年布雷顿森林体系的组织,主要功能是各国货币和货币政策协调,出了一个报告,据说这个报告,相关的小组工作了好长一段时间。但是在今天推出来,就让我有很大的兴趣来读一下。我相信和我有同样兴趣的会有不少。这更让我相信比特币应该是一个谋略。而不是一种自然产生的东西。因为就在美联储主席在国会山作证,说出比特币是一种类似黄金的价值存储之后,IMF的报告就来了。为啥不早不迟的。呵呵。这是一个不一般的事情。

数字货币的崛起

支付宝、天平座、M-Pesa、Paxos、稳定币等等,所有的,或者还有更多其他的,正在我们消费者的数字钱包(数字货币钱包,只是一个钱包意义上的软件,并非真实的钱包,但是意义是一样的)里增加,这也让政策制定者大脑里增加对这种数字货币的事情。但是,我们要如何看待这种数字形式的钱?它们真的是钱吗?这会是一件重要的事情吗?它们真的会因为快速进入应用而对我们有益吗?如果真的是这样,暗示着什么意思呢?首先,它们对银行业的影响可能是什么-如今人们习惯于在哪里创造和管理资金?央行又会有什么反应。是否有机会从这些快速转变中获益,还是仅仅需要进行监管?

本文为解决这些问题迈出了第一步。鉴于其复杂性,它限制了分析的范围,不涉及规范性领域。本文的目的是提供一个概念框架,对新的数字货币进行分类,确定它们的一些风险,考虑其影响,并为中央银行提供一些可供考虑的政策选择。重点主要是新形式的货币与银行部门之间的相互作用,从而关注金融稳定和消费者保护。其他风险和影响——涉及金融完整性、货币政策和资本流动以及反垄断——都是顺带提及的,但并不代表讨论的核心。

简而言之,该文认为,当今两种最具代表性的货币形式将面临严峻的竞争,甚至可能被超越。现金和银行存款将与电子货币相抗衡,电子货币以欧元、美元或人民币等共同记账单位计价并与其挂钩。越来越流行的电子货币形式是稳定的。电子货币作为一种支付手段可能更为方便,但其价值的稳定性却颇受质疑。毕竟,这在经济上类似于一只私人投资基金,以票面价值保证赎回。如果10欧元入账,10欧元就必须出来。发行人必须能够履行这一承诺。

银行将感受到来自电子货币的压力,但应该能够通过提供更有吸引力的服务或类似产品来应对。不过,政策制定者应该做好准备,迎接银行业务格局的一些混乱。如今,在支付领域的新进入者可能有一天会成为银行,并根据他们获得的信息提供有针对性的信贷。因此,银行模式本身不太可能消失。

各国央行将在塑造这一未来方面发挥重要作用。他们制定的规则将对采用新的数字货币产生重大影响,并影响到商业银行的利益——当然,这对商业银行也是如此。一种解决办法是向特定的电子货币供应商提供获得央行准备金的机会,尽管条件严格。这样做会增加风险,但也有不同的优点。同样重要的是,一些国家的央行可以与电子货币提供商合作,有效地提供“中央银行数字货币(Central bank digital currency, CBDC)”,这是一种现金的数字化版本。我们称之为“合成CBDC”。在描绘这些前景的同时,我们强调了在制定具体政策之前仍需要回答的许多问题。

本文共分为四个部分。第一部分回顾了不同的数字货币模型,并提供了一个简单的概念框架来比较和对比它们。第二部分,讨论采用某些新的模式可能非常迅速。尽管没有提供最好的价值存储,但由于网络效应和在线集成,它们作为支付手段的便利性可能是无与伦比的。总之,虽然第一部分提供了变化的分类,但本部分得出结论,有些变化仍然存在。第三部分,论述了数字货币的使用对银行业的潜在影响。它考虑了三个情景:一个是数字货币作为补充,一个是代用品,但银行能够有效地竞争存款,另一个是银行在大量存款外流后转化为私人投资基金。还简要介绍了其他风险。第四部分,也是最后一部分,讨论央行可能如何应对。它讨论了允许一些数字货币提供者持有中央银行储备的潜在好处,并认为这可能为向公众介绍CBDC提供一个有效的模式。

新数字形式的货币

“你的咖啡多少钱?”一欧元,一美元,十元。….不管价格如何,我们都可以拿出当地的纸币和硬币来结账。或者,我们可以刷一张卡片,或者挥动一下手机,就像我们确信咖啡已经付了钱一样就走了。另一个世纪的人会认为这是魔法。事实上,它几乎是。隐藏在视线之外的步骤极其复杂,涉及信息交换、法律和监管结构以及资金的后端结算。然而,我们对此不以为然。

如果有人走进同一家咖啡店,用稳定币支付,或者通过一个社交短信应用程序付费,该怎么办?还是以黄金或其他安全流动性资产(如美国国库券)为后盾的数字代金券?我们会觉得自己像另一个世纪的来访者吗?

为了理解这些新的支付技术,引入一个通用的词汇表和概念框架是很有用的。我们在下一节中提出了一个建议。在此背景下,下一节简要介绍了现有和未来可能的支付手段。

分类学——货币树

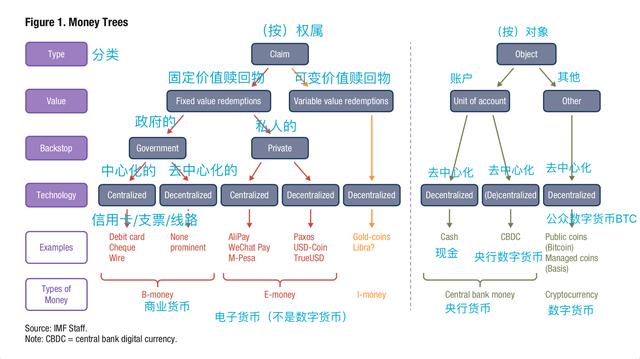

我们通过一个简单的概念框架来比较和对比不同的支付方式。我们强调支付方式的四个属性:类型、价值、后盾和技术。图1讨论了这问题,并在图1中作了说明。由于它的分支结构,我们将其称为“货币树”,它是从Bech和Garratt(2017)在货币经济学中最初使用的植物学类比中借来的。(他们的“金钱花”是我们框架的基础,的确,有些花在树上开花了!)

定义支付方式的第一个属性是”类型”——也是(按)权属或(按)对象。用于支付前面提到的咖啡的现金是基于对象的支付方式的一个例子。只要当事人认为该交易是有效的,交易就会立即结算。没有必要交换信息。另一种选择是转移对其他地方现有价值的权属。如果咖啡是用借记卡支付的,情况就是这样。刷卡会给出指令,将银行资产的所有权从一个人转移到另一个人身上。

按权属的支付简化了交易,但需要复杂的基础设施。在文艺复兴时期,随着按权属为基础的系统的出现,商人们可以方便地携带来自银行的信用证前往国外兑换货物,而不是在钱包中携带沉重和高风险的金币。今天,大多数付款都是按权属为基础的。这些要求付款人被承认为其提出的权属的合法所有人,确定足够的资金支持该债权,并要求所有有关各方对转让进行登记。

支付方式的第二个属性是价值。在对债权进行分类时,有关的问题是以货币权属债权是按固定或可变的价值进行的。固定价值权属保证赎回按预先确定的面值计算单位。对于付款,这一有用的功能使交易各方能够很容易地就他们在有关帐户单位中交换的权属的价值达成协议。例如,以存款的形式向银行索要10欧元可以兑换10欧元的纸币和票据。这些债权类似于债务工具(可能支付利息,也可能不支付利息),可按面值要求赎回。其他类型的债权可以可变价值交换,即按支持索赔的资产的现行市场价值交换。

因此,这种说法类似于股票类工具,既有上行风险,也有下行风险。这些相似之处是为了便于解释,并不一定意味着我们分类为类似债务或类似股权的支付手段将在法庭上得到承认。在对以对象为基础的支付方式进行分类时,有关的问题反而是它们在国内帐户单位或它们自己的帐户单位中的面额。赎回的概念不适用于以对象为基础的支付方式。

付款方式的第三个属性仅适用于以固定价值提出的索赔。问题是,赎回担保是由政府支持,还是仅仅依靠发行人建立的审慎商业惯例和法律结构。在后一种情况下,我们称后台为“私有”。这种区别很重要,因为它可能会影响用户对不同形式货币的信任,以及对监管的反应。最后的属性是技术;定居点是集中的还是分散的?利用集中式技术的事务通过中央专有服务器。使用分散分类账技术(DLT)或块链技术的分散交易在多个服务器之间得到解决。这些可以仅限于信任的少数人(“允许的”网络),或向公众开放(“无权限”)。分散的工具可以更容易地跨越国界。

(笔者按:货币树这一段,只是形象演示人们的支付的不同方式而已。它描述的过于学究式了,只不过是想要仔细厘清各种支付方式之间的不同。我把这张表1放下下面)

文章的原文也放在这里:

Alipay. Libra. M-Pesa. Paxos. Stablecoins. Swish. WeChat Pay. Zelle. All, and many others, are increas- ingly in our wallets as consumers and on our minds

as policymakers. But how should we think of these new digital forms of money? Are they money at all, and does that matter? Will they really benefit from rapid adoption? If so, what might their implications be, on the banking sector to start with—where money is customarily created and managed today? And how might central banks react? Is there an opportunity to benefit from these rapid transformations, or just a need to regulate?

This paper takes a first step in tackling these questions. Given their complexity, it limits the scope of analysis and does not venture into the normative realm. The goal of this paper is to offer a conceptual framework to categorize new digital monies, identify some of their risks, think through the implications, and offer some policy options for central banks to consider. The focus is mostly on the interplay between new forms of money and the banking sector; thus on financial stability and consumer protection. Other

risks and implications—touching on financial integrity, monetary policy and capital flows, and antitrust—are mentioned in passing but do not represent the core of the discussion.

In short, the paper argues that the two most com- mon forms of money today will face tough compe- tition and could even be surpassed. Cash and bank deposits will battle with e-money, electronically stored monetary value denominated in, and pegged to, a common unit of account such as the euro, dollar, or renminbi, or a basket thereof. Increasingly popular forms of e-money are stablecoins. E-money may be more convenient as a means of payment, but ques- tions arise on the stability of its value. It is, after all, economically similar to a private investment fund guaranteeing redemptions at face value. If 10 euros go in, 10 euros must come out. The issuer must be in a position to honor this pledge.

Banks will feel pressure from e-money, but should be able to respond by offering more attractive ser- vices or similar products. Nevertheless, policymakers should be prepared for some disruption in the bank- ing landscape. Today’s new entrants in the payment arena may one day become banks themselves and offer targeted credit based on the information they have acquired. The banking model as such is thus unlikely to disappear.

Central banks will play an important role in mold- ing this future. The rules they set will bear heavily on the adoption of new digital monies, and on the pres- sure these exert on commercial banks. One solution

is to offer selected new e-money providers access to central bank reserves, though under strict conditions. Doing so raises risks, but it also has various advan- tages. Not least, central banks in some countries could partner with e-money providers to effectively provide “central bank digital currency (CBDC),” a digital version of cash. We call this arrangement “synthetic CBDC.” While painting these prospects, we highlight the many questions that still need answers before con- crete policies can be designed.

This paper is organized into four parts. The first reviews the different models of digital money and offers a simple conceptual framework to compare and contrast them. The second part argues that adoption of certain new models may be extremely rapid. Despite not offering the best store of value, their convenience as means of payment could be unrivaled due to network effects and online integration. In short, while the first part offers a taxonomy of change, this part concludes that some changes are here to stay. The third part discusses the potential impact of digital money adoption on the banking sector. It considers three sce- narios: one in which digital monies are complements, one in which they are substitutes but banks are able

to compete effectively for deposits, and one in which banks are transformed into private investment funds following massive deposit outflows. Other risks are also described briefly. The fourth and final part considers how central banks might respond. It discusses the potential benefits of allowing some digital money providers to hold central bank reserves and argues that this could offer an effective model to introduce CBDC to the public at large.

New Digital Forms of Money

“How much for your coffee?” 1 euro, a dollar,

10 yuan . . . Whatever the price, we might pull out local notes and coins to settle the bill. Or we might swipe a card or wave our phone and walk away just as reassured that the coffee was paid for. Someone watching from another century would think it were magic. Indeed, it nearly is. The steps, hidden from view, are extraordinarily complex, involving informa- tion exchange, legal and regulatory structures, as well as back-end settlement of funds. And yet, we think nothing of it.

What if someone walked into the same coffee shop and paid using a stablecoin, or by way of a social messaging app? Or in digital tokens backed by gold or other safe and liquid assets like U.S. Treasury bills? Would we feel like the visitor from another century?

To make sense of these new payment technologies, it is useful to introduce a common vocabulary and conceptual framework. We propose one in the fol- lowing section. Against this backdrop, the subsequent section briefly surveys existing and potential future means of payment.

A Taxonomy—The “Money Tree”

We compare and contrast different means of payment through the lens of a simple conceptual framework. We highlight four attributes of means

of payment: type, value, backstops, and technology.1These are discussed below and illustrated in Figure 1. Because of its branch-like structure, we refer to the figure as the “money tree,” borrowing from Bech and Garratt’s (2017) original use of botanical analogies in monetary economics. (Their “money flower” is com- plementary to our framework; indeed, some flowers blossom on trees!)

The first attribute that defines a means of payment is type—either a claim or an object.2 The cash used to pay for the coffee mentioned earlier is an example of an object-based means of payment. The transaction

is settled immediately as long as the parties deem the object to be valid. No exchange of information is nec- essary. The other option is to transfer a claim on value existing elsewhere. That is the case when coffee is paid for with a debit card. Swiping the card gives instruc- tions to transfer ownership of a claim on bank assets from one person to another.

Claim-based payments simplify transactions, but require a complex infrastructure. With the advent of claim-based systems in the Renaissance, merchants could conveniently travel with letters of credit from their banks and exchange them for goods abroad instead of carrying heavy and risky gold coins in

their purse. Today, most payments are claim-based. These require that payers be recognized as the rightful owners of the claim they offer, that sufficient funds be identified to back the claim, and that the transfer be registered by all relevant parties.

The second attribute of means of payment is value.When classifying claims, the relevant question is whether redemption of the claim in currency is at fixed or variable value. Fixed value claims guarantee redemp- tion at a pre-established face value denominated in

the unit of account. For payments, this useful feature allows parties to a transaction to easily agree on the value of the claim they exchange in the relevant unit of account. For instance, a claim on a bank in the form of deposits for, say, 10 euros can be exchanged for 10 euros worth of bills and notes. These claims resemble debt instruments (which may or may not pay interest) that can be redeemed upon demand at face value. Other types of claims can be exchanged for cur- rency at variable value, meaning at the going market value of the assets that back the claim. Such claims thus resemble equity-like instruments with an upside, but also downside risks. These parallels are intended to facilitate exposition, and do not necessarily imply that the means of payment we classify as debt-like or equity-like would be recognized as such in a court of law. When classifying object-based means of payment, the relevant question instead is their denomination, in the domestic unit of account or their own. The concept of redemption does not apply to object-based means of payment.

文章比较长,我会分几次来把它载完。翻译难免会有做不到位的,欢迎指正。