五种不同的付款方式

上述特征有助于我们区分五种不同的支付方式:(1)中央银行货币;(2)密码货币;(3)b-货币,目前由银行发行;(4)新的私营部门提供者提供的电子货币或电子货币;(5)私人投资基金发行的投资货币(即投资货币的简称)。

最容易辨认的是以现金形式存在的中央银行货币——几个世纪以来我们一直在钱包中携带的纸币和硬币。如前所述,现金是一种基于对象的支付方式。它以当地的记账单位计价,由中央银行发行,在交易各方之间以分散的方式结算,而且明显具有外观。目前,在“中央银行数字货币”(简称cbdc)的标题下,它的数字对立面正在进行辩论。与现金不同,CBDC可能不会匿名,尽管它可以保护用户的数据不受第三方的影响。它的验证技术可以是集中的,也可以是分散的,而且可以提供兴趣。曼奇尼-格里菲利和其他人(2018年)提供了一个详细的审查CBDC的设计和含义。

另一种基于对象的支付方式是加密货币。它以自己的记账单位计价,由非银行创建(或“铸币”),并在区块链上发行,通常为无权限类型。

另一种区分是相关的——创建密码货币的算法是否试图通过在价格高时发行更多货币来稳定其相对于法定货币的价值,以及在价格较低时退出流通货币。我们将这些系统称为“管理硬币”(也有人称之为“算法稳定的价值硬币”)。然而,这一模型还没有得到广泛的测试,尽管已经由一些初创公司提出,比如基础。我们将其他加密货币称为“公共硬币”,包括比特币和以太坊。

以权属为基础的货币最广泛的使用是b-货币,它通常包括商业银行存款。在许多国家,大多数付款需要将资金从一个银行账户转移到另一个银行账户,往往是从一家银行转到另一家银行,并可能跨越国界。如前所述,我们将b-货币与以记账单位计价的类似债务的工具联系在一起,按面值按需求赎回。转账通常是通过中心化的技术进行的,例如借记卡、电汇和支票。

b-货币的主要特点是它的赎回担保得到了政府的支持。当然,谨慎的商业模式有助于满足潜在的赎回请求。但公共政策也起着一定的作用。银行受到监管和严密监管。在监管有效的地方,银行不能承担过多的风险,必须保持充足的流动性。此外,如果银行没有流动资产来满足提款要求,中央银行可以在系统压力下通过隔夜贷款或紧急贷款提供流动性。最后,在许多国家,存款以一定的限额为保险。只要这一保险是可信的,消费者就不会担心他们赎回存款的能力,企业应该得到有效监管的保证。

电子货币正在成为支付领域中的一个重要的新参与者。相对于加密货币而言,电子货币最重要的创新之处是发行可按需求以货币形式赎回的债权(图2)。借用我们之前的类比,它是一种类似债务的工具。这就像b-货币,只是赎回担保不是由政府支持的。它们仅仅取决于对可供赎回的资产的审慎管理和法律保护。转移可以集中进行,就像亚洲和非洲许多流行的支付解决方案一样,包括中国的支付宝和微信支付、印度的Paytm和东非的M-Pesa(也称为“储存价值设施”)。请注意,银行也可以在与客户打交道时发放电子货币,而这些客户并不能从存款保险中受益。基于区块链的电子货币形式——如双子座、帕克斯、T美元和美元币——也正在涌现。这些通常被称为“法币令牌”。“稳定币”一词也被广泛使用,尽管有一个模糊的定义,其中也包括前面讨论过的“管理币”。

最后,货币是一种潜在的新的支付方式,尽管一种可能或不可能从电子货币中取走的支付方式,除了一个非常重要的特点外,相当于电子货币——它提供了可变价值的货币赎回;因此,它是一种类似股票的工具。”I-货币”意味着对资产的索赔,通常是指黄金或投资组合中的股票。黄金为价值基础的有例如数字瑞士黄金(Digital Swiss Gold,DSG)和Novem。

私人投资基金——如货币市场基金和交易所交易基金——提供相对安全和流动性较强的投资,但尚未提供广泛的支付方式。特别是在美国,以市场为基础的金融系统要比传统的银行系统大。私人基金已经开始允许客户付款。然而,这些贷款大多依赖于抵押贷款(信用卡支付),或快速和低成本赎回为法定货币的后续支付。

然而,如今,私人投资基金的股票可能会变成i-money。它们可以被令牌化(令牌一词,就笔者理解就是私钥,也就是一串密码字符),这意味着它们可以用数字分布式账本上任意数量的数字货币来表示。然后,数字货币可以直接以低成本进行交易,并构成以基础投资组合为单位的付款,在投资组合的价值以任何货币计价。(原文:Today, however, shares in private investment funds could become i-money. They can be tokenized, meaning they can be represented by a coin of any amount on a digital ledger. The coin can then be traded directly, at low cost, and constitute a payment denominated in the underlying portfolio, valued at the portfolio’s going worth in any currency. )例如,如果B欠A10欧元,B可以将价值10欧元的货币市场基金转移到A。如果该基金是流动的,那么它的市场价格应该在任何时候都能被知道。如果基金是非常安全的资产,A可以同意持有这些资产,并期望使用这些资产支付未来商品和服务的费用,汇率与当地货币大致相同。换句话说,i-money可能足够稳定,可以作为一种广泛的支付手段。然而,由于国际货币的转移意味着证券所有权的转移,它可能受到监管限制,例如可能限制跨境交易。

一个具体的例子,i-money支持投资组合的资产可能是Libra天秤座,Libra刚刚宣布由Facebook脸书和Libra Association天秤座协会的成员。2019年6月18日公布的天秤座细节仍有待公布。然而,似乎天秤座将得到由银行存单和短期政府票据组成的投资组合(称为天秤座储备)的支持。天秤座数字货币可以在任何时候兑换成法定货币,以换取其在基础投资组合中所占的份额,而无需任何价格担保。这使天秤座有别于e-money(电子化的货币,如支付宝)。天秤座——本质上是天秤座储备的股份——的转让(尽管可能没有合法的索偿要求)将包括支付,就像上面的例子一样。

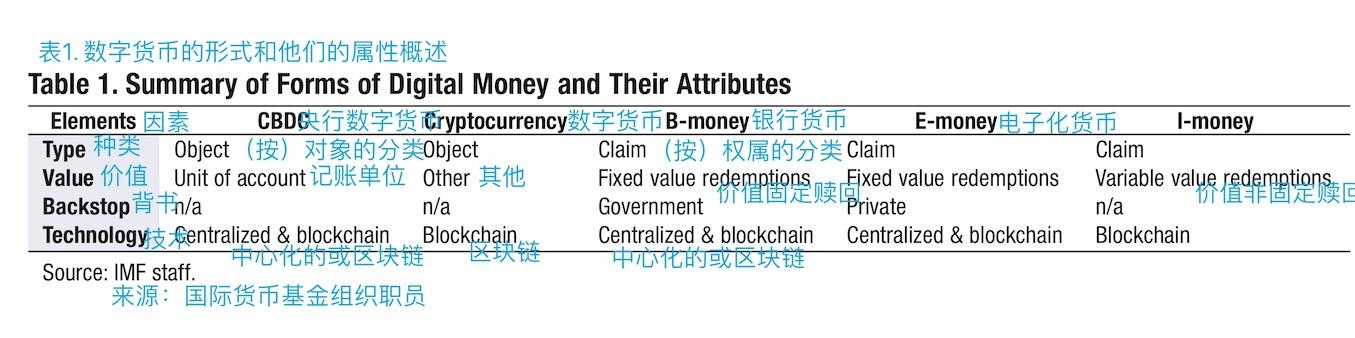

我们提供表1作为不同形式的货币的总览,我们刚刚根据我们的概念框架的四个方面进行了评估。

电子化货币(E-money)的应用可能会加速

如果一种付款方式——无论是权属还是实物——在与用户最相关的帐户单位中具有稳定的价值,则更有可能被广泛采用。首先,各方同意至少持有完成交易所需的时间。此外,它们将更容易就其相对于合同交易价格的价值达成一致,通常以共同记账单位表示。因此,稳定的价值是被广泛用作支付手段的物品或索赔的必要条件。问题是有多稳定?电子化货币能像它的某些竞争形式一样稳定吗?如果没有,它作为一种方便的支付手段的好处是否能够补偿,并仍然导致广泛采用?请注意,我们这里的重点是电子化货币,但许多洞察力可以扩展到I-货币,如果和什么时候它也起飞。(笔者认为就电子货币E-money这个词加一个”化”字,方便区分数字货币和电子货币之间的概念)

Five Different Means of Payment

The above attributes help us distinguish among five different means of payment: (1) central bank money; (2) crypto-currency; (3) b-money, which currently is issued by banks; (4) electronic money, or e-money, offered by new private sector providers; and (5) i-money, short for investment money, issued by private investment funds.

The most recognizable is central bank money in

the form of cash—the notes and coins we have been carrying in our wallets for centuries. As discussed earlier, cash is an object-based means of payment. It is denominated in the local unit of account, is issued by the central bank, is settled in a decentralized fashion among transacting parties, and obviously has physical appearance. Its digital counterpart is currently being debated under the heading of “central bank digital cur- rency,” or CBDC for short. Unlike cash, CBDC would likely not be anonymous, although it could protect users’ data from third parties. Its validation technology could be centralized or decentralized, and it could offer interest. Mancini-Griffoli and others (2018) offers a detailed review of CBDC designs and implications.

The other object-based means of payment is crypto- currency. It is denominated in its own unit of account, is created (or “minted”) by nonbanks, and is issued on a blockchain, commonly of the permissionless type.

An additional distinction is relevant—whether the algorithm underlying the creation of cryptocurrency attempts to stabilize its value relative to fiat currency by issuing more currency when its price is high and withdrawing currency from circulation when its price is low. We refer to these systems as “managed coins” (some also call these “algorithmically stabilized value coins”). However, the model is not yet widely tested, though has been proposed by startups such as Basis. We refer to other cryptocurrencies as “public coins,” including Bitcoin and Ethereum.

The most widespread use of claim-based money

is b-money, which typically covers commercial bank deposits. In many countries, most payments entail the transfer of funds from one bank account to another, often from one bank to another, and possibly across borders. As discussed earlier, we associate b-money with debt-like instruments denominated in a unit

of account, redeemable upon demand at face value. Transfers are most commonly carried out through cen- tralized technologies, as in the case of debit cards, wire transfers, and checks.

The key distinguishing feature of b-money is that its redemption guarantee is backstopped by the govern- ment. Of course, a prudent business model helps meet potential redemption requests. But public policy also plays a role. Banks are regulated and closely super- vised. Where regulation is effective, banks cannot

take excessive risks and must keep ample liquidity. In addition, if banks run out of liquid assets to honor requests for withdrawals, central banks may provide liquidity via overnight loans or emergency facilities in times of systemic stress. Finally, deposits are insured in many countries up to a certain limit. To the extent this insurance is credible, consumers do not worry about their ability to redeem their deposits, and businesses should be reassured by effective regulation.

E-money is emerging as a prominent new player in the payments landscape. Its single most important innovation relative to cryptocurrencies is to issue claims that can be redeemed in currency at face value upon demand (Figure 2). Borrowing from our earlier analogy, it is a debt-like instrument. It is like b-money except that redemption guarantees are not backstopped by governments. They merely rest on prudent man- agement and legal protection of assets available for redemption. Transfers can be centralized, as in the case of many of the popular payment solutions in Asia and Africa, including Alipay and WeChat Pay in China, Paytm in India, and M-Pesa in East Africa (also called “stored value facilities”). Note that banks can also issue e-money to the extent they deal with clients that do not benefit from deposit insurance. Blockchain-based forms of e-money—such as Gemini, Paxos, TrueUSD, and USD Coin by Circle and Coinbase—are also popping up. These are often referred to as “fiat tokens.” The term “stablecoin” is also widely used, though suffers from a vague definition which also covers the “managed coins” discussed earlier.

Finally, i-money is a potential new means of pay- ment, though one which may or may not take off. I-money is equivalent to e-money, except for a very important feature—it offers variable value redemptions into currency; it is thus an equity-like instrument. I-money entails a claim on assets, typically a com- modity such as gold or shares of a portfolio. Exam- ples of gold-backed i-money are Digital Swiss Gold (DSG) and Novem.Private investment funds—such as money market funds, and exchange-traded funds—offering relatively safe and liquid investments have been growing rapidly but do not yet offer widespread means of payment.

In the United States in particular, the market-based financial system is larger than the traditional banking system. Private funds have begun allowing clients to make payments. However, these have relied mostly on collateralized lending (credit card payments) or rapid and low-cost redemptions into fiat currency for subse- quent payments.

Today, however, shares in private investment funds could become i-money. They can be tokenized, meaning they can be represented by a coin of any amount on a digital ledger. The coin can then be traded directly, at low cost, and constitute a payment denominated in the underlying portfolio, valued at the portfolio’s going worth in any currency. For instance, if B owes A 10 euros, B could transfer 10 euros worth of a money market fund to A. To the extent that the fund is liquid, its market price should be known at any point in time. And to the extent the fund com- prises very safe assets, A may agree to hold these with the expectation of using these to pay for future goods and services at approximately the same exchange rate with local currency. In other words, i-money could be sufficiently stable to serve as a widespread means of payment. However, as the transfer of i-money entails

a transfer of ownership of securities, it may be subject to regulatory restrictions that could limit transactions across borders, for instance.

A tangible example of i-money backed by a port- folio of assets may be Libra, the coin just announced by Facebook and members of the Libra Association. Details on Libra, announced June 18, 2019, are still to be released. However, it seems as if Libra would

be backed by a portfolio (called Libra Reserves) made up of bank certificates of deposit and short-term government paper. Libra coins could be exchanged into fiat currency at any time for their share of the going value of the underlying portfolio, without any price guarantees. This sets Libra apart from e-money.

The transfer of Libra—essentially shares of Libra Reserves (though potentially without a legal claim)— would comprise a payment, just as in the

above example.

We offer Table 1 as a summary of the different forms of money we just evaluated along the four ele- ments of our conceptual framework.

Adoption of E-money Could Be Rapid

If a means of payment—either claim or object—has stable value in the unit of account most relevant to users, it is much more likely to be widely adopted.

For one, parties will agree to hold it at least for the time it takes to complete the transaction. In addi- tion, they will more easily agree on its value relative

to the contracted transaction price, usually expressed

in a common unit of account. Stable value is thus a necessary condition for an object or claim to be widely used as a means of payment. The question is how stable? And can e-money be as stable as some of its competing forms of money? If not, can its advantages as a convenient means of payment compensate and still lead to widespread adoption? Note that we focus here on e-money, but many of the insights could extend to i-money if and when it also takes off.

笔者按:读这种科学化的分类和分类的理由一般会显得很枯燥。但是大致能了解到专业人员是怎么界定和看待其本质的。